Unfreezing and Transfer Learning in Deep Learning

Since we know that a convolutional neural network consists of many linear layers with a nonlinear activation function between each pair, followed by one or more final linear layers with an activation function such as softmax at the very end. The final linear layer uses a matrix with enough columns such that the output size is the same as the number of classes in our model (assuming that we are doing classification). This final linear layer is unlikely to be of any use for us when we are fine-tuning in a transfer learning setting, because it is specifically designed to classify the categories in the original pretraining dataset. So when we do transfer learning, we remove it, throw it away, and replace it with a new linear layer with the correct number of outputs for our desired task.

This newly added linear layer will have entirely random weights. Therefore, our model prior to fine-tuning has entirely random outputs. But that does not mean that it is an entirely random model! All of the layers prior to the last one have been care‐ fully trained to be good at image classification tasks in general. The first few layers encode general concepts, such as finding gradients and edges, and later layers encode concepts that are still useful for us, such as finding eye‐ balls and fur.

We want to train a model in such a way that we allow it to remember all of these generally useful ideas from the pretrained model, use them to solve our particular task (classify pet breeds, for instance), and adjust them only as required for the specifics of our particular task. Our challenge when fine-tuning is to replace the random weights in our added linear layers with weights that correctly achieve our desired task (classifying pet breeds) without breaking the carefully pretrained weights and the other layers. A simple trick can allow this to happen: tell the optimizer to update the weights in only those ran‐ domly added final layers. Don’t change the weights in the rest of the neural network at all. This is called freezing those pretrained layers.

This is where fastai shines!

I love fastai for these kind of amazing features.

When we create a model from a pretrained network, fastai automatically freezes all of the pretrained layers for us. When we call the fine_tune method, fastai does two things:

-

Trains the randomly added layers for one epoch, with all other layers frozen

-

Unfreezes all the layers, and trains them for the number of epochs requested

Although this is a reasonable default approach, it is likely that for your particular dataset, you may get better results by doing things slightly differently. The fine_tune method has parameters you can use to change its behavior.

So let’s try doing this manually ourselves. First of all, we will train the randomly added layers for three epochs, using fit_one_cycle.

learn = cnn_learner(dls, resnet34, metrics=error_rate)

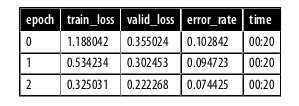

learn.fit_one_cycle(3, 3e-3)

Then we’ll unfreeze the model:

learn.unfreeze()

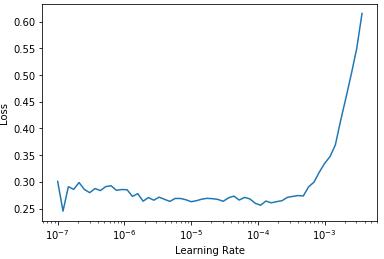

and run lr_find, because having more layers to train, and weights that have already been trained for three epochs, means our previously found learning rate isn’t appropriate anymore:

learn.lr_find()

Our model has been trained already. Here we have a somewhat flat area before a sharp increase, and we should take a point well before that sharp increase—for instance, 1e-5.

Let’s train at a suitable learning rate:

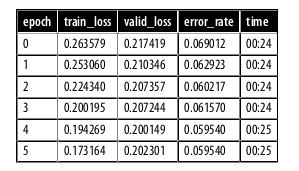

learn.fit_one_cycle(6, lr_max=1e-5)

This has improved our model a bit, but there’s more we can do. The deepest layers of our pretrained model might not need as high a learning rate as the last ones, so we should probably use different learning rates for those—this is known as using discriminative learning rates(Not to be discussed here).

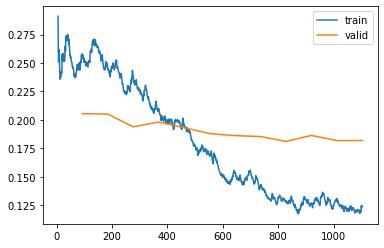

fastai can show us a graph of the training and validation loss:

learn.recorder.plot_loss()

As you can see, the training loss keeps getting better and better. But notice that eventually the validation loss improvement slows and sometimes even gets worse! This is the point at which the model is starting to overfit. In particular, the model is becoming overconfident of its predictions. But this does not mean that it is getting less accurate, necessarily. Take a look at the table of training results per epoch, and you will often see that the accuracy continues improving, even as the validation loss gets worse. In the end, what matters is your accuracy, or more generally your chosen metrics, not the loss. The loss is just the function we’ve given the computer to help us to optimize.

Conclusion

Unfreezing and transfer learning play a crucial role in deep learning by offering a powerful solution to the challenge of training complex models with limited labeled data. By leveraging pre-trained models, which have learned general concepts from extensive datasets, we can save substantial computational resources and time. Unfreezing the pre-trained layers allows us to adapt the model’s knowledge to a specific task, enabling it to specialize and improve performance on new data. Transfer learning enables us to harness the wealth of information captured by pre-trained models and apply it effectively to novel problems, making it an indispensable technique for accelerating model development and achieving state-of-the-art results in various domains.